Table of Contents

Last Updated on December 29, 2020 by IDS Team

Getting into the world of music takes more than just learning music theory and proper technique.

Whatever is the instrument of your choice – guitar, piano, violin, or even your vocal cords – there are so many aspects that you’ll first need to get into in order to get your tone right.

Especially with an instrument like an electric guitar where setting up your tone requires extensive research and sometimes even years of experience.

In fact, many have literally turned this into a scientific field, and there are actual engineers working on designing and tweaking pedals, rack-mounted units, and other effects.

We could easily say that being a good musician these days, especially a guitar player, is a combination of music theory knowledge, tight technique, knowledge of how pedals work, and experience.

With all these traits checked out, you’ll be able to know when to apply which effect for a particular genre or a situation.

With all this being said, we’ll be getting into some “secrets” about one of the most important effects in the world of modern music – distortion.

The iconic Boss DS-2 Turbo distortion pedal

Although often associated with guitars and rock music, you can find the effect used, one way or another, with other instruments and various genres.

Of course, EDM musicians will also use distortion, mostly as vst plugins, although it’s not uncommon for some DJs to even implement guitar distortion pedals in their setup.

The same could be said for some solo string players, like violinists or cellists, who like to mingle and experiment with these effects.

The particular issue that we’re getting into has caused confusion among many musicians over the years.

We all know about overdrive, distortion, and fuzz pedals. We’re also somewhat aware of their sonic properties.

But there must have been at least one moment where you wondered about what are the actual distinctions between these three effects.

If you’re having trouble understanding the difference between overdrive, distortion, and fuzz – worry not! After this guide, you’ll get familiar with some of the technical details and will also know how to implement these effects the proper way and in required situations to perfectly fit your style. So let’s get into it.

What you need to know first

Before jumping into the technical details of how these three effects work, there are a few things you need to know first.

We don’t want you to end up with more questions than answers.

The first important thing you need to know is that all of these three effects are actually distortion by definition.

Look at it as an umbrella term for these three distinct types of effects. Yes, this might get a bit confusing since among these three we also have an effect labeled as “distortion.”

This subcategory of distortion, that’s also named “distortion,” is just a widely accepted (dare we say commercial?) name for an effect that’s achieved by heavy clipping.

We’ll get into all these details in a few moments, but what you now need to know first is that distortion, as an audio signal processing effect, is divided into three widely accepted commercial categories – overdrive, distortion, and fuzz.

Now that we have this part covered, a few other things you need to know. Below, we’ll be explaining a thing or two about the clean signal, what headroom means, what’s clipping, and how the musicians back in the old days achieved.

Clean signal

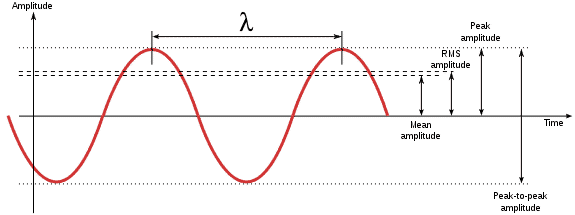

Let’s take the ordinary unprocessed clean guitar tone.

This kind of signal can be represented as one smooth continuous sine curve.

Now we get into a physics aspect of it.

The signal has its wavelength, which is the length of one peak of the sine curve to the next one, and peak-to-peak amplitude, which is the height of the curve from one peak to the other.

What we’re interested here is the amplitude.

The more you push the volume, the “wider” the peak-to-peak amplitude gets.

This means that a louder signal will have a bigger amplitude compared to a quieter one.

To fully grasp this, here’s a graphic representation of a continuous sine curve with all the important elements marked on it.

source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sinus_amplitude_en.svg

Clipping

The next thing we’ll be explaining here is the process of clipping.

Every device that you play through – be it an amp, pedal, or a mixing console – has its limitations.

You can’t just increase the amplitude to infinity and beyond and expect it to sound the same, only louder.

At one point, the signal going from your instrument will get too loud for the device that you’re playing through and it will ultimately get “clipped.”

This means that both the top and the bottom of the wave get cut or “clipped” and you end up with that broken-sounding tone.

Instead of getting louder and louder, the amplifier or a pedal cuts the signal and turns into that “buzzing” mess.

Below, you can see a graphic representation of what clipping looks like:

source: https://lithiumgrim.jouwweb.nl/blog/319712_headroom-say-what

As you can see, by increasing the amplitude, the signal eventually reached the limitations of a certain device – let’s say a pedal.

It appears almost as if someone literally clipped off the top and the bottom ends of the otherwise perfect-looking smooth sine curve.

Now we get to the most important part.

By doing this “clipping,” the resulting tone gets distorted. Most of the distortion pedals achieve the effect through a 2-step process.

- Step 1- the original signal is amplified through the so-called operational amplifiers (or op-amps for short) which are integrated within the circuit.

- Step 2- this amplified signal is clipped using the transistors or diodes, depending on the type of pedal. The whole point of these components is to bring the threshold down and clip off the signal.

We should also mention that there are symmetrical and asymmetrical types of clipping.

The clipping is usually done by two diodes or two transistors, one clipping the bottom end of the sine curve, and the other one the top end.

If you have two different types of diodes and transistors, they cut the signal unequally on top and the bottom, causing irregular wave shapes.

This is referred to as asymmetrical clipping and can be found with some overdrives these days, usually as a switchable mode.

Headroom

What you also need to understand is the concept of “headroom.”

In the above section, we explained how the limitations, or a threshold, of a certain device, like an amp or a pedal, cause clipping and distortion.

The headroom represents the “space” between the peak of your clean signal and your amp’s or pedal’s threshold.

In this area, the signal will be “safe” from any clipping or distortions. Depending on the device’s purpose and design, they can either have larger all smaller headroom.

How they did it in the old days

Now it’s time to sit back, relax, and get into the history of the distortion effect.

Back in the old days, the late 1940s and the early 1950s, it wasn’t exactly easy to achieve any kind of distortion.

What’s more, there was somewhat of a disagreement between guitar players and engineers. The first group loved that dirty distorted tone and always did their best to find any means to achieve it.

The latter group, the engineers, looked down upon clipping and distortion as if these were their arch enemies. To them, the distortion was an error.

Since all of the guitar amps in that era were tube-based, the guitar players noticed that by pushing the volume control to some “dangerous” territories, the tone would get all distorted.

But it wasn’t exactly the kind of distortion we hear today. It was more of an ambitious competition between the guitar players and bands to sound louder and more unique. It was just a slight coloration, something like a milder yet ear-piercing overdrive these days.

There are a few early examples from the late 1940s of distortion being used in popular songs at the time.

But arguably one of the best-known examples is “Bob Wills Boogie” by Bob Willis. His guitar player at the time, Robert Junior Barnard, pushed the amp over its limits and got that “hot” and slightly distorted tone. Maybe not exactly heavy by today’s standards, but it was still pretty exciting for the era. You can listen to the song below:

As time went by, guitar players found more and more ways to distort their tone.

However, some of the distorted tones on singles and records were a result of happy accidents.

One of the most prominent of those accidents comes from 1951 and it happened to a guitarist named Willie Kizart.

Playing with Ike Turner and the Kings of Rhythm, the group was all set to record a tune named “Rocket 88” in the studio.

Unfortunately, Kizart’s amp got damaged in transport and, of course, the tone suffered. He was left with no choice but to record using what he had at the moment. But surprisingly enough, the resulting tone turned the song into a hit.

After this, everyone was trying to replicate the buzzing sound, marking the beginning of a true revolution in modern music.

As a result, many began deliberately damaging their amplifiers to achieve the effect, making it a trend that continued well into the mid-1960s.

In 1960, Marty Robins and his band entered the studio to record a song called “Don’t Worry.” It’s not certain whether it was the idea of the engineer there or Marty’s guitar player Grady Martin, but the guitar was recorded through a faulty channel on the mixer.

The resulting solo was pretty heavy for that era. The song was released in 1961 to critical acclaim.

Going further, there were some other examples of distorted guitar in popular music, with some musicians even getting in touch with engineers to help them create distortion devices.

However, the first commercially available distortion pedal was FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone, released in 1962 by Gibson under their subsidiary brand Maestro.

This device, initially marketed as some sort of a proto “multi-effects” piece, only got more attention after Keith Richards implemented it for The Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction“, which was released in 1965.

The iconic FZ-1 Fuzz Tone pedal by Gibson

It’s too bad that no one told the guys from The Kinks about the pedal since they resorted to slashing the speaker of an innocent amp to record 1964’s “You Really Got Me.”

Well, at least they achieved a great distorted tone and went down in history for being one of the pioneers of modern rock and hard rock music.

Later in the 1960s and the early 1970s, guitar players used the potential and properties of their tube amps to get a distorted tone, with companies deliberately making it easier for them.

Some guys like Deep Purple’s Ritchie Blackmore or Black Sabbath’s Tony Iommi used a clean booster, Dallas Arbiter’s Rangemaster.

This way, they pushed the signal and made it hit the threshold of their amplifiers more easily, achieving more clipping and distortion in the process. This particular method is being used even to this day, mostly by those who are fans of vintage-oriented tones.

The 1970s saw the rise of guitar pedals as we know them today.

Thanks to the invention of transistors and their implementation in the music equipment, the distortion became easier to achieve.

Of course, there’s the unavoidable mention of the piece like Fuzz Face by Dallas Arbiter from the late 1960s, a pedal that’s being produced to this day by Dunlop Manufacturing Inc.

Fuzz Face by Dallas Arbiter. source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FuzzFace_Effect_Pedal.jpg

And this was really the golden age for guitar distortion.

Some of these same circuits, with some components improved or altered, are still being made.

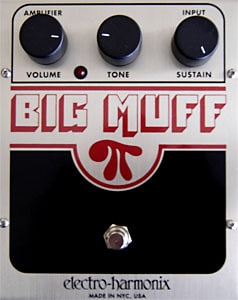

There’s the Boss DS-1 Distortion that made its debut in the late 1970s, as well as the revolutionary Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi from the early 1970s. Another piece that also changed the game was Ibanez’s iconic Tube Screamer, developed from Maxon’s old OD808.

These are just some of the examples of pedals that came into the spotlight and helped guitar players change the course of history.

During the 1970s and the 1980s, we got the final distinction between the three types of distortion that we’ll be discussing today.

So how are they different? Let’s find out.

Overdrive

First, we start with the overdrive, the “mildest” of the three.

Many beginners, or even novice players, look down upon overdrives as distortions with less gain.

However, this is far from an exact definition of overdrives and how they work.

In fact, their tone has very little to do with the amount of saturation but rather how it is achieved.

The difference comes down to the type of clipping.

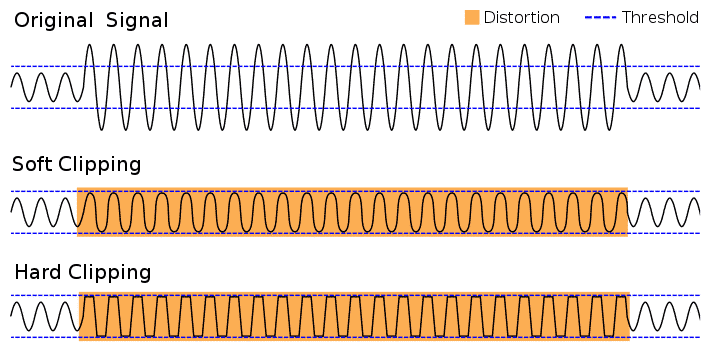

First, with overdrive, we have the so-called “soft” clipping. The sine curve of the clean signal is cut in a softer manner and the shape of this new clipped waveform has no rough edges. The resulting tone often resembles what you would get by pushing the old amplifiers over their limits. The only difference here is that you usually don’t get any kind of dynamic response with just the overdrive pedal.

Here’s a simplified example of the difference between soft and hard clipping.

source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clipping_waveform.svg

The soft clipping in overdrive pedals is usually achieved through diodes, while the classic distortion or fuzz pedals use transistors. There are three types of diodes – silicone, germanium, and LED-based.

Overdrive pedals can often be seen used in pair with tube amplifiers.

This way, the overdrive pedals serve as a boost that will further push the limits of the tube amp and cause its own “organic” clipping.

In addition, there’s clipping going on in the pedal itself, which will add some coloration to the overall tone.

Overdrive pedals can even be used paired with dirty channels of tube amps to create natural-sounding tones in the high gain areas. This is exactly why many metal players have been using Ibanez Tube Screamer or Maxon OD808. Another great example would be Zakk Wylde and his signature MXR ZW-44 Overdrive pedal.

As for those milder tones, a piece like Boss OD-1 or BD-2 Blues Driver works well with clean channels of both tube and solid-state amplifiers. Their soft clipping and a somewhat muffled tone come as a great solution for vintage-inspired bluesy tones.

Distortion

What guitar players and other musicians often refer to as “distortion” is the distortion effect with hard clipping.

This nomenclature might cause some confusion since the subcategory of the effect bears the same name. However, we can clearly hear the distinction and tell it apart from overdrives.

The classic guitar distortion effect has that “fried” or “scorched” tone, going into more “dangerous” territories while keeping the tightness.

The clean signal gets processed through operational amplifiers and transistors, just like with overdrive pedals. However, the signal here gets cut abruptly, causing the wave to get sharply distorted.

While there is certainly an abundance of different distortions, this particular effect is usually associated with hard rock and heavy metal music, along with most of the subdivisions of these genres.

Famous pedals that come to mind are Boss DS-1, Boss MT-2, MXR Distortion Plus, TC Electronic Dark Matter, Pro Co RAT, just to name a few.

Compared to overdrives, hard clipping of distortion pedals is most often achieved using transistors.

The most often type of a transistor you can find these days is silicon-based, although there are some rare instances of germanium ones.

Fuzz

If you really want to go off the charts and have a psychedelic-drenched tone, then get yourself a fuzz pedal.

The closest thing we can find to describe the fuzz effect is a broken amplifier, similar to the tone achieved in the above mentioned “Don’t Worry” by Marty Robbins.

The main distinction that makes fuzz different from other types of distortions is pretty simple – it features extreme clipping.

The waveform is so distorted that it resembles a square shape. This way, you not only get a very “disfigured” tone, but also a very rich harmonic content. This effect is usually achieved without the use of operational amplifiers, but rather just transistors doing extreme clipping.

However, fuzz is not for everyone’s liking. It’s mostly present in psychedelic rock, blues rock, or stoner and doom rock music, and is usually not the favorite choice of classic virtuoso shred-type guitar players. Nonetheless, the effect requires very tight technique and great control over your playing. You don’t want to get anything wrong with the fuzz effect turned on.

The first commercial fuzz pedal was the Maestro FZ-1. Other famous examples include the well-known Big Muff Pi, the legendary and very rare Univox Super-Fuzz, as well as the Fuzz Face which was originally produced by Dallas Arbiter.

The Big Muff Pi. source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EHPi.jpg

The Fuzz Face got some significant popularity due to the fact that Jimi Hendrix used it back in the day.

This same model, with some changes in the circuit (the inclusion of silicone instead of a germanium transistor) and the overall design, is now manufactured by Dunlop.

What about boost?

You should not confuse boost with distortion pedals.

Boosters just amplify the signal without any clipping done inside the pedal.

They come in handy paired with tube amps, letting them do all the organic-sounding clipping and helping them achieve distortion on their own.

They’re not exactly the most exciting devices, but they have their purpose.

What you should also know

Technically speaking, a clipped signal is pretty close to a dynamically compressed one.

Compressors increase the volume of quiet parts and decrease the volume of louder parts, making the overall output dynamically more even.

The distortion itself comes with some compression with it, ultimately making an impact on the dynamic response of your guitar tone.

The harsher the distortion and the harder the clipping, the more compressed your tone will get.

What’s the best option for me?

The choice of the right distortion comes down to your personal preferences, the style of music, and the types of guitars and amplifiers that you have.

Overdrives usually work best for old school type of stuff, although you’ll find them in pedalboards of modern metal players who use them for enhancing the tone of their tube amps. Giving the softer, mellow, yet mid-range oriented tone, they’re a great option if you use clean channels of tube amplifiers.

Distortions are a classic choice for any hard rock and metal player. Whether you’re playing through a solid-state or a tube amplifier, they’ll always be able to create those scorched yet controlled tight tones for both rhythm and lead playing. They’re the most popular choice for most of the genres these days.

Fuzz effect is a bit tricky and is for those with very specific tastes. First off, it’s not easy to have things under control with a fuzz pedal on, and it’s mostly useful for single notes. Having a rich harmonic content, playing power chords with a fuzz pedal might not be the best choice, especially if there is more than one guitar in the band. It’s mostly a choice for stoner, doom, psychedelic, and blues-rock guitar players.

But at the end of the day, we are not bound by any laws and written rules.

You’re always free to experiment and go outside of the conventional boundaries of any genre.

However, knowing some of the rules and old trends will help you in your creative endeavors and you’ll be able to create a better tone for a given situation.